Water Charity with Friendly Water for the World put on a 9-day training program and conference in Gisenyi, Rwanda in January 2017. The technology taught was the construction and maintenance of rainwater catchment systems, with a focus on Ferro-cement tanks. The conference and training were a great success, and publication of the conclusion was delayed until the results, including the spin-off effect, could be fully evaluated.

To read about the beginning of the project, CLICK HERE.

Water Charity and Friendly Water for the World Take on the Long Walk for Water

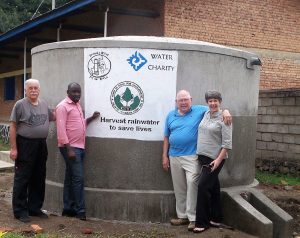

With generous grants from Water Charity and the Leiter Family Foundation, Friendly Water for the World organized a nine-day training program in Gisenyi, Rwanda in building rainwater catchment systems, using Ferro-cement tanks. There were 41 people from seven countries, including Water Charity’s Chief Operating Officer, Averill Strasser, and Executive Director, Beverly Rouse. Hosted by Friendly Water’s partner organization Hand in Hand for Development, trainers came from the Friendly Water affiliate in Uganda, where they have been using the technology for three years.

Background: Two major water issues face people in much of the developing world, especially in rural areas: access and quality. In some way, they are really one issue, because a lack of consistent access to clean water is one of the most critical causes of extreme poverty in East and Central Africa. The costs in mortality and morbidity from waterborne illnesses are vast and are especially acute in rural areas where there is little access to health care. Families are engaged in a never-ending cycle of trips to doctors and hospitals, and a search for pharmaceuticals, which are then often taken with the very water that made family members ill to begin with. Child mortality is particularly high, which, besides being linked to funeral expenses, also results in women having more children, as grown children are the only safety net an elderly family may have. Lack of access to clean water defeats efforts at education and micro-finance schemes as community development strategies to improve people’s lives.

While in certain areas, water from rivers, streams, and lakes is plentiful, elsewhere it is only available seasonally, or not at all. In volcanic areas, the soil will not hold water. In others, relatively shallow wells are dug, and re-dug. In Kenya and Uganda, it is estimated that 70% of shallower wells fail within three years. In other areas, deep wells bring up dangerous levels of fluoride and other naturally occurring contaminants, often leaving children crippled or mentally challenged.

“The Long Walk to Water” represents the reality that women and children in most of the developing world walk on average four miles each day to collect water, water that will often make their families sick. Even in places where water may be plentiful, the long walk to water remains. Five hours a day may be spent in the collection and preparation of water, rendering other occupations for women difficult if not impossible. Children, especially girls, are taken out of school at early to collect water. Education is disrupted, and it is estimated that in certain parts of sub-Saharan Africa, female literacy rates are actually declining. During the long walk to the water, girls are in many instances at high risk of rape and sexual assault.

Without clean water, the impact of providing education as a strategy to end poverty is circumscribed. A study undertaken by Friendly Water for the World found that, in many areas, children enrolled in school are absent on average two out of every five days because of waterborne illnesses. In addition, girl children are much more likely to drop out of school at puberty because of the lack of clean water and sanitary facilities. But even worse, without clean water, young children ages 1-5 spend precious energy that should be going into brain development fighting off waterborne parasites. This condition, called “Parasitic Stress”, often renders children permanently unable to learn effectively even if they get to school.

Among the trainees were 12 young adults – half men, half women – from western Rwanda, comprising two teams of six each. Most of them had been orphaned in the Rwandan genocide of 1994.

In the nine days, under close supervision, the trainees built both a 20,000-liter and a 5,000-liter tank. Participants learned how to estimate the water needed to support a household or a group of households through a dry season and to design a catchment system to meet that specific need. In addition, trainees learned to build “water hives”, smaller, 2,000-3,000-liter tanks constructed in a single day, using a prefabricated internal mold. Water hives are particularly useful as sanitation stations at schools, or in rainy climates where, nonetheless, an enclosed vessel for capturing rainwater can assist in keeping water clean. Coupled with BioSand Water Filters, rainwater catchment is the gold standard for clean and accessible water. In Rwanda, Ferro-cement tanks cost only 40% of the cost of plastic ones and will last twice as long.

The two catchment teams, equipped with tools by Friendly Water, now have orders for more than 25 systems, valued at more than $40,000. They have already conducted a five-day training of a group from Kibumba, Congo-DRC, who hope to build some 100 water hives. Once the teams have a broader range of experience, they will be prepared to travel throughout east and central Africa, building new systems, and setting up new fabrication teams.

Meanwhile, the 5,000-liter tank is immediately being put to good use! The Tunywamazimeza (“Use Clean Water”) group (Gisenyi, Rwanda) – a group of 20 HIV+ widows, many with children, who have now built and sold more than 2,200 BioSand Water Filters, is using the water from the tank to clean sand and mix the concrete for the Filters. No more walk for water! (and no paying for it either).